When Bjorn Lomborg wrote

When Bjorn Lomborg wrote

“Green

Cars Have a Dirty Little Secret” for The Wall Street

Journal earlier this month, he based his argument—that

electric vehicles (EVs) are no better for the environment than

internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) due to the

manufacturing process—on

a 2012 study published by the Journal of Industrial Ecology

(JIE). He made a convincing case, and I must admit:

I was taken in.

But the convenience and even wide-spread belief of something

doesn’t necessarily make it true. Spurred on to seek out the truth

by a very helpful Reason reader, I took a hard look at the

JIE study from Hawkins et al.

I wasn’t the first to do this, but I hope to be one who cares

more about the facts than an agenda.

As it turns out, the JIE study that Lomborg points to contains a

number of problems that should raise a quizzical scientific

eyebrow. In fact, Hawkins et al. were forced to issue a

correction to their report in January.

In the JIE correction, EVs come out much greener than they do in

Lomborg’s op-ed. While Lomborg states that “unless the electric car

is driven a lot, it will never get ahead

environmentally,” Hawkins et al. come to a different

conclusion:

We find that EVs powered by the European electricity mix reduce

GWP [global warming potential] by 26% to 30% relative to gasoline

(originally 20% to 24%) and 17% to 21% relative to diesel

(originally 10% to 14%).

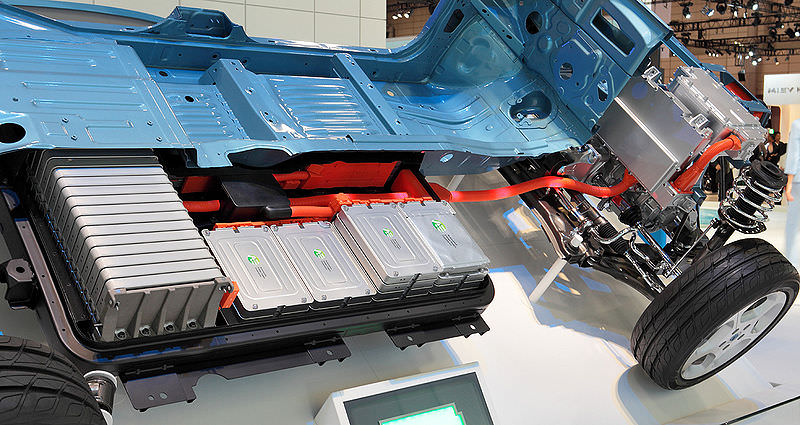

Even in the original study, EVs came out ahead over an estimated

lifespan of 90,000 miles, despite being loaded down with

lithium-ion batteries that scientific advancements have not yet

made kind to Mother Nature. Still, reducing emissions by up to 30%

without necessitating any changes to our current energy consumption

habits can hardly be called “never getting ahead.”

And that’s assuming that

And that’s assuming that

Hawkins et al. have actually reached a reasonable conclusion now

that they have corrected their estimates of the required production

inputs for a Nissan Leaf—their representative EV for the study.

Instead of assuming, however, let’s take a look at another

study.

This UCLA report prepared for the California Air Resources

Board,

Lifecycle Analysis Comparison of a Battery Electric Vehicle and a

Conventional Gasoline Vehicle, compares EVs (which they refer

to as BEVs, or battery electric vehicles) to ICEVs (which they call

CVs, or conventional gasoline vehicles). On pages 18 and 19, the

authors report average expected CO2 emissions over a lifetime of

180,000 miles for an ICEV to be more than twice those

expected for an EV.

In sum: both the JIE and the UCLA studies reach very similar

conclusions. Hawkins et al. find EVs to be up to 30 percent cleaner

than ICEVs over 90,000 miles and the UCLA study estimates 64

percent lower CO2 emissions over 180,000. (Keep in mind: this is

with current battery technology as well as current energy mixes,

which rely primarily on fossil fuels.)

And yet Lomborg dismisses this still-fledgling technology as

doing “virtually nothing.” He’s right that EVs are not “zero

emissions,” of course. But if the chief goal of a buyer is to

reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they are a step in the right

direction.

That having said, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions isn't

grounds for thousands of dollars in subsidies from Uncle Sam. Let

the market decide if it's worth driving an electric car to be

green, not the government.

UPDATE (3:00 pm): Bjorn Lomborg reached out to

me via email with this response that I think is worth posting:

I do know of the correction to the Hawkins study, but it

just changes the outcome about 6% (they're very explicit about it

not changing much). However, the US electricity grid is also

significantly more co2-intensive than the EU average, which was why

I kept their estimate of 24% less emissions if driven 90,000 miles

in my WSJ. It is not surprising, that if the car

is driven twice that at 180,000 miles, it will emit even

less.My point with the WSJ article, however, was also to point out

that if you can only drive 73 miles at a time (and likely much

less, both because you want to avoid being stranded, like NYTimes

reporter John Broder, and because the range declines to 55 miles in

five years), it is much less likely that you

will drive even 90,000 miles and certainly 180,000 miles before you

change your battery and hence increase your co2 emissions

again.Moreover, if you buy a car with a longer range (just drove a

fantastic Tesla with almost 300 miles range)—its batteries will

obviously have emitted so much more co2 in production that it is

unlikely the car will ever earn it back.So, I don't think these points serve to undermine my argument,

but rather simply show that the numbers are pretty clear. If you

drive little (50,000 miles or less), you'll emit more co2. If you

drive rather much (90,000 miles) you'll probably emit 76% of a

gasoline car (with average US electricity), and if you drive your

electric car exceptionally far (180,000 miles) you might just emit

half of a gasoline car.All that remains to think about is how far will most future

purchasers of a Nissan Leaf actually drive their car. Most will buy

it as their second car for short, infrequent trips.

This is an excellent point. In writing this post, I focused

solely on rebutting the idea that EVs can't make up for their

manufacture with lower greenhouse gas emissions over time (and

miles). I stand by what I've written above—they can even with

current technology. If you drive them long enough.

However, Lomborg's point that many will buy these as second cars

and use them only rarely and for short trips is probably very true.

If you're buying one of these cars to reduce your emissions, you

better actually drive it a lot (instead of your ICEV) and hold onto

it for as long as possible. Otherwise they're just a wasteful

fashion statement—like pretty much every other car on the road.

0 σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου